The Yemeni Fragments

In this clash of symbols, the impact of the Yemeni Fragments deserves to be watched. It could be way bigger in significance than the Dead Sea Scrolls:

Effectively meaningless.

Let that sink in.

This is because, literally,

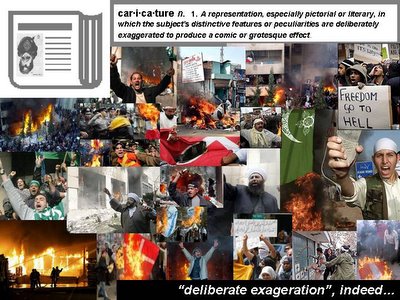

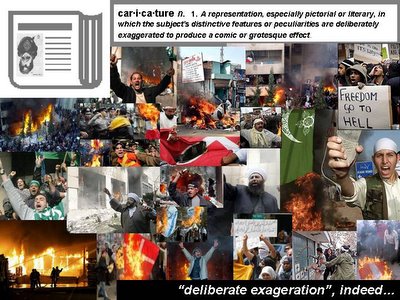

Oh, you mean like this?

IN 1972, during the restoration of the Great Mosque of Sana'a, in Yemen, laborers working in a loft between the structure's inner and outer roofs stumbled across a remarkable gravesite, although they did not realize it at the time. Their ignorance was excusable: mosques do not normally house graves, and this site contained no tombstones, no human remains, no funereal jewelry. It contained nothing more, in fact, than an unappealing mash of old parchment and paper documents -- damaged books and individual pages of Arabic text, fused together by centuries of rain and dampness, gnawed into over the years by rats and insects. Intent on completing the task at hand, the laborers gathered up the manuscripts, pressed them into some twenty potato sacks, and set them aside on the staircase of one of the mosque's minarets, where they were locked away -- and where they would probably have been forgotten once again, were it not for Qadhi Isma'il al-Akwa', then the president of the Yemeni Antiquities Authority, who realized the potential importance of the find.This aspect cannot be underestimated:

...

Some of the parchment pages in the Yemeni hoard seemed to date back to the seventh and eighth centuries A.D., or Islam's first two centuries -- they were fragments, in other words, of perhaps the oldest Korans in existence. What's more, some of these fragments revealed small but intriguing aberrations from the standard Koranic text. Such aberrations, though not surprising to textual historians, are troublingly at odds with the orthodox Muslim belief that the Koran as it has reached us today is quite simply the perfect, timeless, and unchanging Word of God.

THE first person to spend a significant amount of time examining the Yemeni fragments, in 1981, was Gerd-R. Puin, a specialist in Arabic calligraphy and Koranic paleography based at Saarland University, in Saarbrücken, Germany. Puin, who had been sent by the German government to organize and oversee the restoration project, recognized the antiquity of some of the parchment fragments, and his preliminary inspection also revealed unconventional verse orderings, minor textual variations, and rare styles of orthography and artistic embellishment. Enticing, too, were the sheets of the scripture written in the rare and early Hijazi Arabic script: pieces of the earliest Korans known to exist, they were also palimpsests -- versions very clearly written over even earlier, washed-off versions. What the Yemeni Korans seemed to suggest, Puin began to feel, was an evolving text rather than simply the Word of God as revealed in its entirety to the Prophet Muhammad in the seventh century A.D.Working quietly for years, maintaining a low profile to avoid having their investigation halted by the Yemeni authorities, the German scholars finally finished their catalog:

...

To date just two scholars have been granted extensive access to the Yemeni fragments: Puin and his colleague H.-C. Graf von Bothmer, an Islamic-art historian also based at Saarland University.

Von Bothmer, however, in 1997 finished taking more than 35,000 microfilm pictures of the fragments, and has recently brought the pictures back to Germany. This means that soon Von Bothmer, Puin, and other scholars will finally have a chance to scrutinize the texts and to publish their findings freely -- a prospect that thrills Puin. "So many Muslims have this belief that everything between the two covers of the Koran is just God's unaltered word," he says. "They like to quote the textual work that shows that the Bible has a history and did not fall straight out of the sky, but until now the Koran has been out of this discussion. The only way to break through this wall is to prove that the Koran has a history too. The Sana'a fragments will help us to do this."You can say that again!

Puin is not alone in his enthusiasm. "The impact of the Yemeni manuscripts is still to be felt," says Andrew Rippin, a professor of religious studies at the University of Calgary, who is at the forefront of Koranic studies today. "Their variant readings and verse orders are all very significant. Everybody agrees on that. These manuscripts say that the early history of the Koranic text is much more of an open question than many have suspected: the text was less stable, and therefore had less authority, than has always been claimed."

...

"To historicize the Koran would in effect delegitimize the whole historical experience of the Muslim community," says R. Stephen Humphreys, a professor of Islamic studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara. "The Koran is the charter for the community, the document that called it into existence. And ideally -- though obviously not always in reality -- Islamic history has been the effort to pursue and work out the commandments of the Koran in human life. If the Koran is a historical document, then the whole Islamic struggle of fourteen centuries is effectively meaningless."

Effectively meaningless.

Let that sink in.

This is because, literally,

as the Encyclopaedia of Islam (1981) points out, "the closest analogue in Christian belief to the role of the Kur'an in Muslim belief is not the Bible, but Christ." If Christ is the Word of God made flesh, the Koran is the Word of God made text, and questioning its sanctity or authority is thus considered an outright attack on Islam -- as Salman Rushdie knows all too well.Even the "accepted" text is problematic:

The adoption of the doctrine of inimitability was a major turning point in Islamic history, and from the tenth century to this day the mainstream Muslim understanding of the Koran as the literal and uncreated Word of God has remained constant.Maybe it doesn't make sense because it's the ravings of a delusional schizophrenic?

GERD-R. Puin speaks with disdain about the traditional willingness, on the part of Muslim and Western scholars, to accept the conventional understanding of the Koran. "The Koran claims for itself that it is 'mubeen,' or 'clear,'" he says. "But if you look at it, you will notice that every fifth sentence or so simply doesn't make sense. Many Muslims -- and Orientalists -- will tell you otherwise, of course, but the fact is that a fifth of the Koranic text is just incomprehensible. This is what has caused the traditional anxiety regarding translation. If the Koran is not comprehensible -- if it can't even be understood in Arabic -- then it's not translatable. People fear that. And since the Koran claims repeatedly to be clear but obviously is not -- as even speakers of Arabic will tell you -- there is a contradiction. Something else must be going on."

To Wansbrough, the Islamic tradition is an example of what is known to biblical scholars as a "salvation history": a theologically and evangelically motivated story of a religion's origins invented late in the day and projected back in time.Psychopathic Vandalism?

...

Wansbrough's arcane theories have been contagious in certain scholarly circles, but many Muslims understandably have found them deeply offensive. S. Parvez Manzoor, for example, has described the Koranic studies of Wansbrough and others as "a naked discourse of power" and "an outburst of psychopathic vandalism."

Oh, you mean like this?

14 Comments:

Could you give some sources?

http://aeolians.blogspot.com

Yes. It seems the link I originally used, at the top of this post, has gone dead. I will update it.

The article I quoted appeared originally in The Atlantic, called "What is in the Koran", by Toby Lester, from January 1999.

A copy was hosted at wsfi.net, which I linked to, but that site seems gone.

If you can't get premium content (it will just show the first few paragraphs) from The Atlantic, a full copy can be found here and it is reprinted in part of this book.

The Bible, The Qur'an and Science

by Dr. Maurice Bucaille

THE HOLY SCRIPTURES EXAMINED IN THE LIGHT

OF MODERN KNOWLEDGE

Translated from French

by Alastair D. Pannell and The Author

Authenticity of the Qur'an

How It Came To Be Written

Thanks to its undisputed authenticity, the text of the Qur'an holds a unique place among the books of Revelation, shared neither by the Old nor the New Testament. In the first two sections of this work, a review was made of the alterations undergone by the Old Testament and the Gospels before they were handed down to us in the form we know today. The same is not true for the Qur'an for the simple reason that it was written down at the time of the Prophet; we shall see how it came to be written, i.e. the process involved.

In this context, the differences separating the Qur'an from the Bible are in no way due to questions essentially concerned with date. Such questions are constantly put forward by certain people without regard to the circumstances prevailing at the time when the Judeo-Christian and the Qur'anic Revelations were written; they have an equal disregard for the circumstances surrounding the transmission of the Qur'an to the Prophet. It is suggested that a Seventh century text had more likelihood of coming down to us unaltered than other texts that are as many as fifteen centuries older. This comment, although correct, does not constitute a sufficient reason ; it is made more to excuse the alterations made in the Judeo-Christian texts in the course of centuries than to underline the notion that the text of the Qur'an, which was more recent, had less to fear from being modified by man.

In the case of the Old Testament, the sheer number of authors who tell the same story, plus all the revisions carried out on the text of certain books from the pre-Christian era, constitute as many reasons for inaccuracy and contradiction. As for the Gospels, nobody can claim that they invariably contain faithful accounts of Jesus's words or a description of his actions strictly in keeping with reality. We have seen how successive versions of the texts showed a lack of definite authenticity and moreover that their authors were not eyewitnesses.

Also to be underlined is the distinction to be made between the Qur'an, a book of written Revelation, and the hadiths, collections of statements concerning the actions and sayings of Muhammad. Some of the Prophet's companions started to write them down from the moment of his death. As an element of human error could have slipped in, the collection had to be resumed later and subjected to rigorous criticism so that the greatest credit is in practise given to documents that came along after Muhammad. Their authenticity varies, like that of the Gospels. Not a single Gospel was written down at the time of Jesus (they were all written long after his earthly mission had come to an end), and not a single collection of hadiths was compiled during the time of the Prophet.

The situation is very different for the Qur'an. As the Revelation progressed, the Prophet and the believers following him recited the text by heart and it was also written down by the scribes in his following. It therefore starts off with two elements of authenticity that the Gospels do not possess. This continued up to the Prophet's death. At a time when not everybody could write, but everyone was able to recite, recitation afforded a considerable advantage because of the double-checking possible when the definitive text was compiled.

The Qur'anic Revelation was made by Archangel Gabriel to Muhammad. It took place over a period of more than twenty years of the Prophet's life, beginning with the first verses of Sura 96, then resuming after a three-year break for a long period of twenty years up to the death of the Prophet in 632 A.D., i.e. ten years before Hegira and ten years after Hegira. [Muhammad's departure from Makka to Madina, 622 A.D.]

The following was the first Revelation (sura 96, verses 1 to 5) [ Muhammad was totally overwhelmed by these words. We shall return to an interpretation of them, especially with regard to the fact that Muhammad could neither read nor write.].

"Read: In the name of thy Lord who created,

Who created man from something which clings

Read! Thy Lord is the most Noble

Who taught by the pen

Who taught man what he did not know."

Professor Hamidullah notes in the Introduction to his French translation of the Qur'an that one of the themes of this first Revelation was the 'praise of the pen as a means of human knowledge' which would 'explain the Prophet's concern for the preservation of the Qur'an in writing.'

Texts formally prove that long before the Prophet left Makka for Madina (i.e. long before Hegira), the Qur'anic text so far revealed had been written down. We shall see how the Qur'an is authentic in this. We know that Muhammad and the Believers who surrounded him were accustomed to reciting the revealed text from memory. It is therefore inconceivable for the Qur'an to refer to facts that did not square with reality because the latter could so easily be checked with people in the Prophet's following, by asking the authors of the transcription.

Four suras dating from a period prior to Hegira refer to the writing down of the Qur'an before the Prophet left Makka in 622 (sura 80, verses 11 to 16):

"By no means! Indeed it is a message of instruction

Therefore whoever wills, should remember

On leaves held in honor

Exalted, purified

In the hands of scribes

Noble and pious."

Yusuf Ali, in the commentary to his translation, 1934, wrote that when the Revelation of this sura was made, forty-two or forty-five others had been written and were kept by Muslims in Makka (out of a total of 114).

--Sura 85, verses 21 and 22:

"Nay, this is a glorious reading [In the text: Qur'an which also means 'reading'.]

On a preserved tablet"

--Sura 56, verses 77 to 80:

"This is a glorious reading

In a book well kept Which none but the purified teach.

This is a Revelation from the Lord of the Worlds."

--Sura 25, verse 5:

"They said: Tales of the ancients which he has caused to be written and they are dictated to him morning and evening." Here we have a reference to the accusations made by the Prophet's enemies who treated him as an imposter. They spread the rumour that stories of antiquity were being dictated to him and he was writing them down or having them transcribed (the meaning of the word is debatable, but one must remember that Muhammad was illiterate). However this may be, the verse refers to this act of making a written record which is pointed out by Muhammad's enemies themselves.

A sura that came after Hegira makes one last mention of the leaves on which these divine instructions were written:

--Sura 98, verses 2 and 3:

"An (apostle) from God recites leaves

Kept pure where are decrees right and straight."

The Qur'an itself therefore provides indications as to the fact that it was set down in writing at the time of the Prophet. It is a known fact that there were several scribes in his following, the most famous of whom, Zaid Ibn Th�bit, has left his name to posterity.

In the preface to his French translation of the Qur'an (1971), Professor Hamidullah gives an excellent description of the conditions that prevailed when the text of the Qur'an was written, lasting up until the time of the Prophet's death:

"The sources all agree in stating that whenever a fragment of the Qur'an was revealed, the Prophet called one of his literate companions and dictated it to him, indicating at the same time the exact position of the new fragment in the fabric of what had already been received . . . Descriptions note that Muhammad asked the scribe to reread to him what had been dictated so that he could correct any deficiencies . . . Another famous story tells how every year in the month of Ramadan, the Prophet would recite the whole of the Qur'an (so far revealed) to Gabriel . . ., that in the Ramadan preceding Muhammad's death, Gabriel had made him recite it twice . . . It is known how since the Prophet's time, Muslims acquired the habit of keeping vigil during Ramadan, and of reciting the whole of the Qur'an in addition to the usual prayers expected of them. Several sources add that Muhammad's scribe Zaid was present at this final bringing-together of the texts. Elsewhere, numerous other personalities are mentioned as well."

Extremely diverse materials were used for this first record: parchment, leather, wooden tablets, camels' scapula, soft stone for inscriptions, etc.

At the same time however, Muhammad recommended that the faithful learn the Qur'an by heart. They did this for a part if not all of the text recited during prayers. Thus there were Hafizun who knew the whole of the Qur'an by heart and spread it abroad. The method of doubly preserving the text both in writing and by memorization proved to be extremely precious.

Not long after the Prophet's death (632), his successor Abu Bakr, the first Caliph of Islam, asked Muhammad's former head scribe, Zaid Ibn Th�bit, to make a copy. this he did. On Omar's initiative (the future second Caliph), Zaid consulted all the information he could assemble at Madina: the witness of the Hafizun, copies of the Book written on various materials belonging to private individuals, all with the object of avoiding possible errors in transcription. Thus an extremely faithful copy of the Book was obtained.

The sources tell us that Caliph Omar, Abu Bakr's successor in 634, subsequently made a single volume (mushaf) that he preserved and gave on his death to his daughter Hafsa, the Prophet's widow.

The third Caliph of Islam, Uthman, who held the caliphate from 644 to 655, entrusted a commission of experts with the preparation of the great recension that bears his name. It checked the authenticity of the document produced under Abu Bakr which had remained in Hafsa's possession until that time. The commission consulted Muslims who knew the text by heart. The critical analysis of the authenticity of the text was carried out very rigorously. The agreement of the witnesses was deemed necessary before the slightest verse containing debatable material was retained. It is indeed known how some verses of the Qur'an correct others in the case of prescriptions: this may be readily explained when one remembers that the Prophet's period of apostolic activity stretched over twenty years (in round figures). The result is a text containing an order of suras that reflects the order followed by the Prophet in his complete recital of the Qur'an during Ramadan, as mentioned above.

One might perhaps ponder the motives that led the first three Caliphs, especially Uthman, to commission collections and recensions of the text. The reasons are in fact very simple: Islam's expansion in the very first decades following Muhammad's death was very rapid indeed and it happened among peoples whose native language was not Arabic. It was absolutely necessary to ensure the spread of a text that retained its original purity. Uthman's recension had this as its objective.

Uthman sent copies of the text of the recension to the centres of the Islamic Empire and that is why, according to Professor Hamidullah, copies attributed to Uthman exist in Tashkent and Istanbul. Apart from one or two possible mistakes in copying, the oldest documents known to the present day, that are to be found throughout the Islamic world, are identical; the same is true for documents preserved in Europe (there are fragments in the Biblioth�que Nationale in Paris which, according to the experts, date from the Eighth and Ninth centuries A.D., i.e. the Second and Third Hegirian centuries). The numerous ancient texts that are known to be in existence all agree except for very minor variations which do not change the general meaning of the text at all. If the context sometimes allows more than one interpretation, it may well have to do with the fact that ancient writing was simpler than that of the present day. [ The absence of diacritical marks, for example, could make a verb either active or passive and in some instances, masculine or feminine. More often than not however, this was hardly of any great consequence since the context indicated the meaning in many instances.]

The 114 suras were arranged in decreasing order of length; there were nevertheless exceptions. The chronological sequence of the Revelation was not followed. In the majority of cases however, this sequence is known. A large number of descriptions are mentioned at several points in the text, sometimes giving rise to repetitions. Very frequently a passage will add details to a description that appears elsewhere in an incomplete form. Everything connected with modern science is, like many subjects dealt with in the Qur'an, scattered throughout the book without any semblance of classification.

* It is imporatnt to say that Qur'an was collected during the Prophet's lifetime. The Prophet, and before his death, had showed the collection of Qur'an scrolls to Gabriel many times. So, what is said in regard to collecting of Qur'an during the ruling period of the Caliphs after the Prophet means copying the same original copy written in the Prophet's life which later were sent to different countries, and it does not mean the recording or writing of Qur'an through oral sources as it may be thought. Yet, many of the Companions have written the Qur'an exactly during the lifetime of the Prophet. One of those was Imam Ali's copy. He, because of his close relation with the Prophet, his long companionship, didn't only collect the dispersed scrolls of the Qur'an, but he rather could accompany it with a remarkable Tafseer, mentioning the occasion of each verse's descension, and was regarded the first Tafseer of Qur'an since the beginning of the Islamic mission. Ibn Abi Al-Hadeed says," All the scholars agree that Imam Ali is the first one who collected the Qur'an," (see Sharhul Nahj, 271). Another one, Kittani, says that Imam Ali could arrange the Qur'an according to each surah's order of descension, (see Strategic Administration, 461). Ibn Sireen Tabe'ee relates from 'Ikrimeh, who said that 'lmam Ali could collect the Qur'an in a manner that if all mankind and jinn gathered to do that, they could not do it at all,' (see al-Itqan 1157-58). Ibn Jizzi Kalbi also narrates, "If only we could have the Qur'an which was collected by Ali then we could gain a lot of knowledge," (see al-Tasheel, 114). That was only a brief note about the benefits of Imam Ali's Mus'haf, as Ibn Sireen had declared, "I searched so long for Imam Ali's Mus'haf and I correspounded with Medina, but all my efforts gone in vain.' (see al-Itqan, 1/58, al-Tabaqat,2/338). Thus; it becomes certain that Qur'an has been collected by Imam Ali without simple difference between it and other known copies, except in the notes mentioned by Him which renders it as the most excellent copy has ever been known. Unfortunately, the inconvenient political conditions emerged after the demise of the Prophet, (i.e after the wicked issue of Saqeefah) was a main obstacle to get benefits from that remarkable copy of the Qur'an.

http://www.witness-pioneer.org/vil/Books/MB_BQS/15authenticity.htm

Revelation Of The Qur'an In Seven Ahrûf

It is a well-known fact that there are seven different ahrûf in which the Qur'an was revealed. In the Islamic tradition, this basis can be traced back to a number of hadîths concerning the revelation of the Qur'an in seven ahrûf (singular harf). Some of the examples of these hadîths are as follows:

From Abû Hurairah:

The Messenger of God(P) said: "The Qur'an was sent down in seven ahruf. Disputation concerning the Qur'an is unbelief" - he said this three times - "and you should put into practice what you know of it, and leave what you do not know of it to someone who does."[1]

From Abû Hurairah:

The Messenger of God(P) said: "An All-knowing, Wise, Forgiving, Merciful sent down the Qur'an in seven ahruf."[2]

From cAbdullâh Ibn Mascud:

The Messenger of God(P) said: "The Qur'an was sent down in seven ahruf. Each of these ahruf has an outward aspect (zahr) and an inward aspect (batn); each of the ahruf has a border, and each border has a lookout."[3]

The meaning of this hadîth is explained as:

As for the Prophet's(P) words concerning the Qur'an, each of the ahruf has a border, it means that each of the seven aspects has a border which God has marked off and which no one may overstep. And as for his words Each of the ahruf has an outward aspect (zahr) and an inward aspect (batn), its outward aspect is the ostensive meaning of the recitation, and its inward aspect is its interpretation, which is concealed. And by his words each border ...... has a lookout he means that for each of the borders which God marked off in the Qur'an - of the lawful and unlawful, and its other legal injunctions - there is a measure of God's reward and punishment which surveys it in the Hereafter, and inspects it ...... at the Resurrection ......[4]

And in another hadîth cAbdullâh Ibn Mascud said:

The Messenger of God(P) said: "The first Book came down from one gate according to one harf, but the Qur'an came down from seven gates according to seven ahruf: prohibiting and commanding, lawful and unlawful, clear and ambiguous, and parables. So, allow what it makes lawful, proscribe what it makes unlawful, do what it commands you to do, forbid what it prohibits, be warned by its parables, act on its clear passages, trust in its ambiguous passages." And they said: "We believe in it; it is all from our Lord."[5]

And Abû Qilaba narrated:

It has reached me that the Prophet(P) said: "The Qur'an was sent down according to seven ahruf: command and prohibition, encouragement of good and discouragement of evil, dialectic, narrative, and parable."[6]

These above hadîths serve as evidence that the Qur'an was revealed in seven ahruf. The defination of the term ahruf has been the subject of much scholarly discussion and is included in the general works of the Qur'an. The forms matched the dialects of following seven tribes: Quraysh, Hudhayl, Thaqîf, Hawâzin, Kinânah, Tamîm and Yemen. The revelation of the Qur'an in seven different ahruf made its recitation and memorization much easier for the various tribes. At the same time the Qur'an challenged them to produce a surah like it in their own dialect so that they would not complain about the incomprehensibility.

For example, the phrase 'alayhim (on them) was read by some 'alayhumoo and the word siraat (path, bridge) was read as ziraat and mu'min (believer) as moomin.[7]

Difference Between Ahrûf & Qirâ'ât

It is important to realize the difference between ahruf and Qirâ'ât. Before going into that it is interesting to know why the seven ahruf were brought down to one during cUthmân's(R) time.

The Qur'an continued to be read according to the seven ahruf until midway through Caliph 'Uthman's rule when some confusion arose in the outlying provinces concerning the Qur'an's recitation. Some Arab tribes had began to boast about the superiority of their ahruf and a rivalry began to develop. At the same time, some new Muslims also began mixing the various forms of recitation out of ignorance. Caliph 'Uthman decided to make official copies of the Qur'an according to the dialect of the Quraysh and send them along with the Qur'anic reciters to the major centres of Islam. This decision was approved by Sahaabah and all unofficial copies of the Qur'an were destroyed. Following the distribution of the official copies, all the other ahruf were dropped and the Qur'an began to be read in only one harf. Thus, the Qur'an which is available through out the world today is written and recited only according to the harf of Quraysh.[8]

Now a few words on Qirâ'ât:

A Qirâ'ât is for the most part a method of pronunciation used in the recitations of the Qur'an. These methods are different from the seven forms or modes (ahruf) in which the Qur'an was revealed. The seven modes were reduced to one, that of the Quraysh, during the era of Caliph 'Uthman, and all of the methods of recitation are based on this mode. The various methods have all been traced back to the Prophet(P) through a number of Sahaabah who were most noted for their Qur'anic recitations. That is, these Sahaabah recited the Qur'an to the Prophet(P) or in his presence and received his approval. Among them were the following: Ubayy Ibn K'ab, 'Alee Ibn Abi Taalib, Zayd Ibn Thaabit, 'Abdullah Ibn Mas'ud, Abu ad-Dardaa and Abu Musaa al-Ash'aree. Many of the other Sahaabah learned from these masters. For example, Ibn 'Abbaas, the master commentator of the Qur'an among the Sahaabah, learned from both Ubayy and Zayd.[9]

The transmission of the Qur'an is a mutawâtir transmission, that is, there are a large number of narrators on each level of the chain. Dr. Bilaal Philips gives a brief account of the history of recitation in his book:

Among the next generation of Muslims referred to as Taabe'oon, there arose many scholars who learned the various methods of recitation from the Sahaabah and taught them to others. Centres of Qur'anic recitation developed in al-Madeenah, Makkah, Kufa, Basrah and Syria, leading to the evolution of Qur'anic recitation into an independent science. By mid-eighth century CE, there existed a large number of outstanding scholars all of whom were considered specialists in the field of recitation. Most of their methods of recitations were authenticated by chains of reliable narrators ending with the Prophet(P). Those methods which were supported by a large number of reliable narrators on each level of their chain were called Mutawaatir and were considered to be the most accurate. Those methods in which the number of narrators were few or only one on any level of the chain were refered to as shaadhdh. Some of the scholars of the following period began the practice of designating a set number of individual scholars from the pervious period as being the most noteworthy and accurate. By the middle of the tenth century, the number seven became popular since it coincided with the number of dialects in which the Qur'an was revealed.[10]

The author went on to say:

The first to limit the number of authentic reciters to seven was the Iraqi scholar, Abu Bakr Ibn Mujâhid (d. 936CE), and those who wrote the books on Qirâ'ah after him followed suit. This limitation is not an accurate reprensentation of the classical scholars of Qur'anic recitation. There were many others who were as good as the seven and the number who were greater than them.[11]

Concerning the seven sets of readings, Montgomery Watt and Richard Bell observe:

The seven sets of readings accepted by Ibn-Mujâhid represent the systems prevailing in different districts. There was one each from Medina, Mecca, Damascus and Basra, and three from Kufa. For each set of readings (Qirâ'a), there were two slightly different version (sing. Riwaya).

Other schools of Qirâ'ât are of:

Abû Jacfar Yazîd Ibn Qacqâc of Madinah (130/747)

Yacqûb Ibn Ishâq al-Hadramî of Basrah (205/820)

Khalaf Ibn Hishâm of Baghdad (229/848)

Hasan al-Basrî of Basrah (110/728)

Ibn Muhaisin of Makkah (123/740)

Yahyâ al-Yazîdî of Basrah (202/817)

Conditions For The Validity Of Different Qirâ'ât

Conditions were formulated by the scholars of the Qur'anic recitation to facilitate critical analysis of the above mentioned recitations. For any given recitation to be accepted as authentic (Sahih), it had to fulfill three conditions and if any of the conditions were missing such a recitation was classified as Shâdhdh (unusual).

The first condition was that the recitation have an authentic chain of narration in which the chain of narrators was continuous, the narrators were all known to be righteous and they were all knwon to possess good memories. It was also required that the recitation be conveyed by a large number of narrators on each level of the chain of narration below the level of Sahaabah (the condition of Tawaatur). Narrations which had authentic chains but lacked the condition of Tawaatur were accepted as explanations (Tafseer) of the Sahaabah but were not considered as methods of reciting the Qur'an. As for the narrations which did not even have an authentic chain of narration, they were classified as Baatil (false) and rejected totally.

The seond condition was that the variations in recitations match known Arabic grammatical constructions. Unusual constructions could be verified by their existence in passages of pre-Islamic prose or poetry.

The third condition required the recitation to coincide with the script of one of the copies of the Qur'an distributed during the era of Caliph cUthmân. Hence differences which result from dot placement (i.e., ta'lamoon and ya'lamoon) are considered acceptable provided the other conditions are met. A recitation of a construction for which no evidence could be found would be classified Shaadhdh. This classification did not mean that all aspects of the recitation was considered Shaadhdh. it only meant that the unverified constructions were considered Shaadhdh.[13]

The Chain Of Narration Of Different Qirâ'ât

In this section, the chain of narration or isnad of each Qirâ'ât will be presented. It is worth noting that the chains of narration here are mutawâtir.

Qirâ'a from Madinah: The reading of Madinah known as the reading of Nâfic Ibn Abî Nacîm (more precisely Abû cAbd ar-Rahmân Nâfic Ibn cAbd ar-Rahmân).

Nâfic died in the year 169 H. He reported from Yazîd Ibn al-Qacqâc and cAbd ar-Rahmân Ibn Hurmuz al-'Araj and Muslim Ibn Jundub al-Hudhalî and Yazîd Ibn Român and Shaybah Ibn Nisâ'. All of them reported from Abû Hurayrah and Ibn cAbbâs and cAbdallâh Ibn 'Ayyâsh Ibn Abî Rabî'ah al-Makhzûmî and the last three reported from Ubayy Ibn Kacb from the Prophet(P).[14]

From Nâfic, two major readings came to us : Warsh and Qâlûn.

Qirâ'a from Makkah: The reading of Ibn Kathîr (cAbdullâh Ibn Kathîr ad-Dârî):

Ibn Kathîr died in the year 120 H. He reported from cAbdillâh Ibn Assa'ib al-Makhzûmî who reported from Ubayy Ibn Kacb (The companion of the Prophet(P)).

Ibn Kathîr has also reported from Mujâhid Ibn Jabr who reported from his teacher Ibn cAbbâs who reported from Ubayy Ibn Kacb and Zayd Ibn Thâbit and both reported from the Prophet(P).[15]

Qirâ'a from Damascus: From ash-Shâm (Damascus), the reading is called after cAbdullâh Ibn cAamir.

He died in 118 H. He reported from Abû ad-Dardâ' and al-Mughîrah Ibn Abî Shihâb al-Makhzûmî from cUthmân.[16]

Qirâ'a from Basrah: The reading of Abû cAmr from Basrah:

(According to al-Sabcah, the book of Ibn Mujâhid page 79, Abû cAmr is called Zayyan Abû cAmr Ibn al-cAlâ'. He was born in Makkah in the year 68 and grew up at Kûfah.) He died at 154 H. He reported from Mujâhid and Sacîd Ibn Jubayr and 'Ikrimah Ibn Khâlid al-Makhzûmî and 'Atâ' Ibn Abî Rabâh and Muhammad Ibn cAbd ar-Rahmân Ibn al-Muhaysin and Humayd Ibn Qays al-cA'raj and all are from Makkah.

He also reported from Yazîd Ibn al-Qacqâc and Yazîd Ibn Rumân and Shaybah Ibn Nisâ' and all are from Madinah.

He also reported from al-'Assan and Yahyâ Ibn Yacmur and others from Basrah.

All these people took from the companions of the Prophet(P).[17]

From him came two readings called as-Sûsi and ad-Dûrî.

Qirâ'a from Basrah: From Basrah, the reading known as

Yacqûb Ibn Ishâq al-Hadramî the companion of Shucbah (again). He reported from Abû cAmr and others.[18]

Qirâ'a from Kûfah:The reading of cAasim Ibn Abî an-Najûd (cAasim Ibn Bahdalah Ibn Abî an-Najûd):

He died in the year 127 or 128 H. He reported from Abû cAbd ar-Rahmân as-Solammî and Zirr Ibn Hubaysh.

Abû cAbd ar-Rahmân reported from cUthmân and cAlî Ibn Abî Tâlib and 'Ubayy (Ibn Kacb) and Zayd (Ibn Thâbit).

And Zirr reported from Ibn Mascud.[19]

Two readings were repoted from cAasim: The famous one is Hafs, the other one is Shucbah.

Qirâ'a from Kûfah: The reading of Hamzah Ibn Habîb (from Kûfah as well)

Hamzah was born in the year 80 H and died in the year 156 H. He reported from Muhammad Ibn cAbd ar-Rahmân Ibn Abî Laylâ (who reads the reading of cAlî Ibn Abî Tâlib (RA), according to the book of Ibn Mujâhid called al-Sabcah - The Seven - page 74) and Humrân Ibn A'yan and Abî Ishâq as-Sabî'y and Mansur Ibn al-Mu'tamir and al-Mughîrah Ibn Miqsam and Jacfar Ibn Muhammad Ibn cAlî Ibn Abî Tâlib from the Prophet(P).[20]

Qirâ'a from Kûfah: The reading of al-'Amash from Kûfah as well:

He reported from Yahyâ Ibn Waththâb from 'Alqamah and al-'Aswad and 'Ubayd Ibn Nadlah al-Khuzâ'y and Abû cAbd ar-Rahmân as-Sulamî and Zirr ibn Hubaysh and all reported from Ibn Mascud.[21]

Qirâ'a from Kûfah: The reading of cAli Ibn Hamzah al-Kisâ'i known as al-Kisâ'i from Kûfah.

He died in the year 189 H. He reported from Hamzah (the previous one) and cIesâ Ibn cUmar and Muhammad Ibn cAbd ar-Rahmân Ibn Abî Laylâ and others.[22]

Now our discussion will be on Hafs and Warsh Qirâ'ât.

Hafs & Warsh Qirâ'ât: Are They Different Versions Of The Qur'an?

The Christian missionary Jochen Katz had claimed that Hafs and Warsh Qirâ'ât are different 'versions' of the Qur'an. A concise and interesting article that the missionary had used to reach such a conclusion can be found in the book Approaches of The History of Interpretation of The Qur'an. Ironically, it contained an article by Adrian Brockett, titled "The Value of Hafs And Warsh Transmissions For The Textual History Of The Qur'an", which sheds some light on various aspects of differences between the two recitations. It is also worth noting that, in contrast to Mr. Katz, Brockett used the word transmission rather than text for these two modes of recitations. Some highlights from the article are reproduced below.

Brockett states:

In cases where there are no variations within each transmission itself, certain differences between the two transmissions, at least in the copies consulted, occur consistently throughout. None of them has any effect in the meaning.[23]

The author demarcates the transmissions of Hafs and Warsh into differences of vocal form and the differences of graphic form. According Brockett:

Such a division is clearly made from a written standpoint, and on its own is unbalanced. It would be a mistake to infer from it, for instance, that because "hamza" was at first mostly outside the graphic form, it was therefore at first also outside oral form. The division is therefore mainly just for ease of classification and reference.[24]

Regarding the graphic form of this transmission, he further states:

On the graphic side, the correspondences between the two transmissions are overwhelmingly more numerous than differences, often even with oddities like ayna ma and aynama being consistently preserved in both transmissions, and la'nat allahi spelt both with ta tawila and ta marbuta in the same places in both transmissions as well, not one of the graphic differences caused the Muslims any doubts about the faultlessly faithful transmission of the Qur'an.[25]

And on the vocal side of the transmission the author's opinion is:

On the vocal side, correspondences between the two transmissions again far and away outnumber the differences between them, even with the fine points such as long vowels before hamzat at-qat having a madda. Also, not one of the differences substantially affects the meaning beyond its own context... All this point to a remarkably unitary transmission in both its graphic form and its oral form.[26]

He also discusses the Muslims' and orientalists' attitude towards the graphic transmission:

Many orientalists who see the Qur'an as only a written document might think that in the graphic differences can be found significant clues about the early history of the Qur'an text - if cUthmân issued a definitive written text, how can such graphic differences be explained, they might ask. For Muslims, who see the Qur'an as an oral as well as a written text, however, these differences are simply readings, certainly important, but no more so than readings involving, for instances, fine differences in assimilation or in vigour of pronouncing the hamza.[27]

Brockett goes so far as to provide examples with which the interested reader can carry out an extended analysis. Thus, he states:

The definitive limit of permissible graphic variation was, firstly, consonantal disturbance that was not too major, then unalterability in meaning, and finally reliable authority.

In the section titled, "The Extent To Which The Differences Affect The Sense", the author repeats the same point:

The simple fact is that none of the differences, whether vocal or graphic, between the transmission of Hafs and the transmission of Warsh has any great effect on the meaning. Many are the differences which do not change the meaning at all, and the rest are differences with an effect on the meaning in the immediate context of the text itself, but without any significant wider influence on Muslim thought.[28]

The above is supported by the following:

Such then is the limit of the variation between these two transmissions of the Qur'an, a limit well within the boundaries of substantial exegetical effect. This means that the readings found in these transmissions are most likely not of exegetical origin, or at least did not arise out of crucial exegetigal dispute. They are therefore of the utmost value for the textual history of the Qur'an.[29]

And interestingly enough the author went on to say:

The limits of their variation clearly establish that they are a single text.[30]

Furthermore, we read:

Thus, if the Qur'an had been transmitted only orally for the first century, sizeable variations between texts such as are seen in the hadîth and pre-Islamic poetry would be found, and if it had been transmitted only in writing, sizeable variations such as in the different transmissions of the original document of the constitution of Medina would be found. But neither is the case with the Qur'an. There must have been a parallel written transmission limiting variation in the oral transmission to the graphic form, side by side with a parallel oral transmission preserving the written transmission from corruption.[31]

The investigation led to another conviction:

The transmission of the Qur'an after the death of Muhammad was essentially static, rather than organic. There was a single text, and nothing significant, not even allegedly abrogated material, could be taken out nor could anything be put in.[32]

Finally, we would like to establish Adrian Brockett's conclusion on this matter:

There can be no denying that some of the formal characteristics of the Qur'an point to the oral side and others to the written side, but neither was as a whole, primary. There is therefore no need to make different categories for vocal and graphic differences between transmissions. Muslims have not. The letter is not a dead skeleton to be refleshed, but is a manifestation of the spirit alive from beginning. The transmission of the Qur'an has always been oral, just as it has been written.[33]

Therefore, it comes as no surprise that Christian missionaries like Jochen Katz find themselves "refleshing" a dead skeleton in order to comply with their missionary program of outright deception. Of course, regular participants in the newsgroups have time and again witnessed Jochen's tiring displays of dialectical acrobatics - the misquoting of references and the juggling of facts. Surprisingly enough, missionary Katz cannot even support his point of view using the reference [23], which undermines his missionary agenda of twisting the facts. The reference [23] has firmly established that:

There is only one Qur'an,

The differences in recitation are divinely revealed, not invented by humans

The indisputable conclusion that the Qur'an was not tampered with.

Recitation Of The Qur'an in Hafs, Warsh & Other Qirâ'ât

A few centuries ago, the Qurra, or reciters of the Qur'an, used to take pride in reciting all seven Qirâ'ât. In light of this fact, we decided to make an informal inquiry into some the Qurra who recite in different Qirâ'ât. Two brothers confirmed the following:

Date: 18 Sep 1997 13:44:37 -0700

From: Moustafa Mounir Elqabbany

Newsgroups: soc.religion.islam

I can confirm that al-Husarî did in fact record the entire Qur'an in Warsh, as I have the recording in my possession. A Somali brother also indicated to me that he has a copy of the Qur'an recited in Al-Doori ('an Abî cAmr) recited, again, by al-Husarî. The Qur'an is very widely read and recorded in Qawloon in Libya and Tunisia, so it shouldn't be difficult to acquire those Qirâ'ât either.

And another brother corroborated the following in a private e-mail:

Date: Mon, 27 Oct 1997 21:59:24 +0100

From: Mohamed Ghoniem

To: Metallica

Subject: Re: readings

Well, before al-Husary, Abdel Bassit Abdus Samad has recorded the entire Qur'an in Warsh and many cassettes and CDs are on sale everywhere in the Egypt and in France as well. I personally have in Cairo many recordings of other readers such as Sayyed Mutawally and Sayyed Sa'eed exclusively in Warsh. I have seen several cassettes in the reading of Hamzah (from Khalaf's way) on sale in Egypt and I have bought a couple of them during this summer. They were recorded by Sheikh 'Antar Mosallam.

Presently, I have got two CDs recorded by Sheikh Abdel Bassit gathering three readings (Hafs, Warsh and Hamzah). These CDs belong to a series of six CDs on sale publicly in France in the fnac stores.

http://www.islamic-awareness.org/Quran/Text/Qiraat/hafs.html#1

Thank you for updating the sources of your post.

http://aeolians.blogspot.com

The day of reckoning for Islam is coming. It will not come in the form of a military threat. It will come when...without much fanfare...a number of books are published by peaceful scholars. They will reveal the conclusions of forensic science, revealing how the Koran was pieced together and the sources it was derived from. The Koran, like any crime, has fingerprints all over it and various other evidence. A forensic reading will bring all this to light. As each day goes by we see new proof that the Koran was invented by the caliphs and others as "a naked discourse of power" and "an outburst of psychopathic vandalism."

As of today, nearly 12,000 lives have been snuffed out by Islamic terrorists since 9/11.

Ironic that their god would allow the koran, something that is supposedly so important for their salvation to be made into bug and goat droppings.

Aiyesha, Mohammad's pre-pubescent "bride", noted in the Hadiths that many saying of Mohammad for the Koran, which should have been collected in the "Recitation", were lost. Because the people who had memorized specific suras had died in battle, and the sayings went with them into oblivion, while other suras were written down on organic materials (leather, bark, papyrus, etc.) which were eaten by passing livestock, accidentally.

So the Koran was "imperfect" from before it was even officially collected, since the material which Aiyesha admitted was lost meant that there would always be fatally uncorrectable lancunae.

The book is flawed, and its followers claims of "perfection" are a fraud.

By this, Islam falls.

Crushed under the weight of a willful self-deception by its pompous, delusional proselytizers.

interesting blog. It would be great if you can provide more details about it. Thanks you

legal transcription

Post a Comment

<< Home